When Environmental Responsibility Gets in the Way of … Environmental Responsibility

Impact assessment or IA – also known as and including environmental assessment, environmental impact assessment, social impact assessment, health impact assessment, and a host of other discipline-specific variations along those lines – involves the critical evaluation of the consequences of past, present, and future development. Most commonly, IA is applied to specific projects to assist decision-makers and the public to understand potential environmental, social, cultural, health, and economic impacts – both positive and negative – and to inform the development of measures to mitigate adverse effects and enhance beneficial outcomes. The scope of IA has expanded from its original focus on the biophysical environment to encompass a broad range of issues reflective of today’s society, including gender and identity, Indigenous rights and interests, and inter-generational health and well-being, among other considerations. As such, IA, when done properly and well, is recognized as a vital tool in promoting sustainable development, and legislative frameworks have evolved to establish robust procedures for IA in many jurisdictions, including Canada.

Unfortunately – ironically, even – today’s IA frameworks, born of well-founded intentions to foster sustainability and protect the natural and human environment, often hinder the advancement of projects that are critical to a sustainable future.

Earlier this week, we saw yet another example of the challenge facing Canada and other jurisdictions trying to advance clean energy transition projects: how do we thread the needle, balancing timely project development with legitimate objectives of environmental and community protection at the local level?

In this example, a regional-level government in Italy chose to require a full impact assessment instead of an available fast-track approval process for a proposed electric car battery recycling facility pilot project at an existing facility, prompting the proponent to consider looking elsewhere for more favourable conditions for its project. This outcome illustrates how even a well-intentioned IA framework can undermine progress towards climate action goals, while also impacting global competitiveness.

When an impact assessment process takes many years to complete, like it does here in Canada, it creates a real barrier to getting so-called “green” projects built, delaying the transition to a more sustainable economy and exacerbating the climate crisis we face. In very practical terms, there is a procedural conflict between what needs to be done to address global climate change – including rapid development and deployment of clean energy-related projects – and what needs to be done to protect local ecosystems and communities from the effects of those projects. The latter, too often, is typically accomplished through a complex process that has proven to be unwieldy and time-consuming, undermining the achievement of the former. This conflict is costing us, in economic opportunity, competitiveness, security, and well-being, both now and, through delayed mitigation of the effects of climate change, in the future.

IA frameworks and other regulatory processes urgently need to be retooled to reconcile these two vital aspects of environmental responsibility. We need to develop and apply more timely and efficient ways to evaluate and implement green projects, drawing on our collective knowledge and experience in assessment – and especially management – of the environmental, social, cultural, health, and economic impacts of development.

There is a tremendous breadth and depth of practical experience in Canada and elsewhere in this regard. We need to leverage this expertise to develop trusted, efficient, and expedited decision-making processes that respect and achieve both our local and global environmental goals.

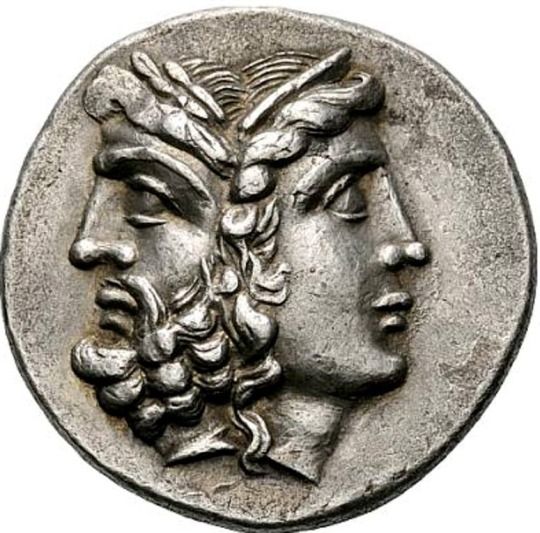

As I was writing this post, I was reminded of Janus, that ancient Roman mythological figure usually depicted with two faces. Janus is known as the god of change and transition, overseeing progress from one time to another, one state or condition to another. Surely there is a metaphor there: these two sides – faces, if you will – of environmental responsibility are part of the whole and both are essential for a successful transition to a clean energy future.