The Long-Awaited List

Today, Prime Minister Carney is scheduled to announce the first tranche of projects to be designated as national interest projects (NIPs) under the new Building Canada Act (BCA). The list is expected to include (based on reporting by CBC and the Globe & Mail):

- expansion of LNG Canada in Kitimat, BC;

- the Darlington New Nuclear Project in Clarington, ON;

- the Contrecœur container terminal project at the Port of Montreal;

- the McIlvenna Bay Copper Mine Project in Saskatchewan; and

- the expansion of the Red Chris Mine in northwestern BC.

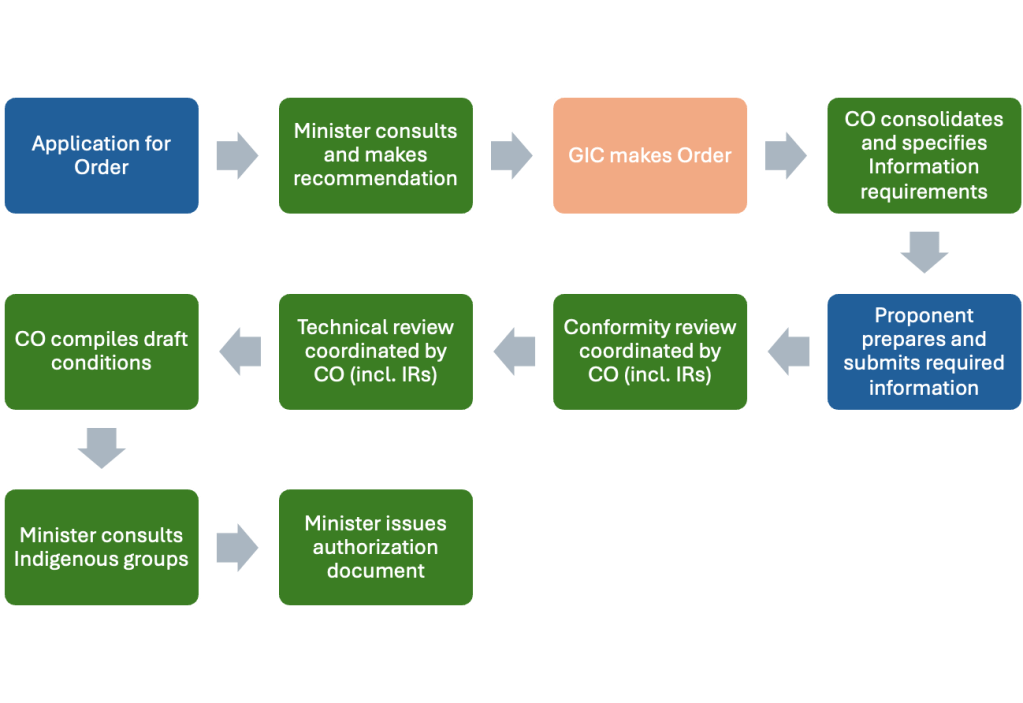

Ostensibly, the point of designation under the BCA is to expedite the federal impact assessment (IA) and permitting process for major projects considered to be of national importance. Viewed in this light, some of the selected projects are a bit puzzling.

The Red Chris Mine expansion, for example, does not actually have any federal legislation triggers according to the proponent’s application to amend its provincial Environmental Assessment Certificate. It’s therefore unclear how NIP designation under the BCA would facilitate this project. British Columbia had already announced, back in February, that it will be fast-tracking the provincial environmental assessment and permitting for this project. (Of note, the expansion will also requires the consent of the Tahltan Central Government pursuant to a decision-making and consent agreement between the Province and that First Nation.)

The McIlvenna Bay mining project is another curious selection. That project is also not subject to a federal IA. It falls below the production threshold specified in the Physical Activities Regulation under the Impact Assessment Act and so is not a ‘designated project’ for the purposes of that Act. Transport Canada has already issued issued an approval under the Canadian Navigable Waters Act for a component of the project. According to the proponent’s provincial environmental impact statement, a Fisheries Act authorization is not required, and its website describes the project as already “permitted” and under construction, so, again, it’s unclear what advantage NIP designation brings to this project.

The Contrecœur project already completed the federal IA process back in 2021, so its designation as a NIP would appear to have no benefit in that regard. However, the proponent, the Montréal Port Authority, only just submitted its application for authorization under the Fisheries Act, so the presumptive approval of that application (as well as any that may be required under the federal Species at Risk Act) may be viewed as the main reason underlying the project’s designation in the first tranche. While the project was deemed not likely to have significant adverse environmental effects (taking mitigation into account) at the IA stage, potential adverse effects on the endangered copper redhorse, a fish species listed in Schedule I of the federal Species at Risk Act, among other fish species of conservation concern, were noted in the assessment report. As it has taken a further 4 ½ years after the IA stage just to complete the Fisheries Act application, let alone securing the actual authorization, the project certainly seems a reasonable candidate for any expediting that NIP designation might afford. It will be interesting to see how long it takes to finalize the federal permitting, especially whether it takes the full two years that has been voiced as the target approval completion timeline for NIPs.

That leaves the LNG Canada expansion and the Darlington New Nuclear Project.

I expect the process for review of the LNG Canada expansion will draw heavily on the outcomes of assessment and permitting already completed for the original project. The federal Decision Statement (the decision document that follows completion of the federal IA process) for the original project was updated as recently as 2021, so the conditions of that decision would likely serve as a solid foundation for establishing conditions for the expansion. This should, in theory, facilitate rapid decision-making even absent NIP designation. With that foundation in place, this will be a true test case to see how quickly the Major Projects Office can get to issuing the deemed authorization decision document under the BCA.

[Interestingly, two other LNG projects that are already in the federal assessment process, the Tilbury LNG Expansion Project and the Ksi Lisims LNG Project, were not designated as NIPs, perhaps because the assessments for those projects are being carried out by BC through a substituted process.]

The Darlington New Nuclear Project completed federal environmental assessment (EA) and secured the site preparation licence from the Canadian Nuclear Safety Commission (CNSC) back in 2012. That licence was renewed in 2021 and site preparation commenced. The proponent, Ontario Power Generation (OPG), applied to the CNSC for a licence to construct the first small modular reactor (SMR) in 2022. However, changes in the proposed nuclear technology since the original EA was completed led CNSC to review the validity of the EA before proceeding with the licence application. The EA was confirmed to be valid in 2024, and the CNSC issued the licence to construct in April 2025. Three additional SMRs are proposed and subject to further licencing by the CNSC. NIP designation of this project will presumably expedite this licencing process, though no light has yet been shed on the process the new Major Projects Office (MPO) will follow in this regard.

[Folks at OPG might be experiencing a bit of déja vu today; through the original Major Projects Management Office (MPMO) initiative, established in 2007 by then PM Harper’s Conservative government, a whole-of-government approach was taken to facilitate the review of the project. A Project Agreement – signed in May 2009 by Natural Resources Canada, CNSC, the then Canadian Environmental Assessment Agency, the Canadian Transportation Agency, Fisheries and Oceans Canada, Transport Canada, Environment Canada, and (then) Indian and Northern Affairs – set out roles and responsibilities and guidelines for the length of each stage of the federal review process, including the EA, Indigenous consultation, and regulatory decision-making. How will the new MPO compare to the MPMO? We wait to see, with bated breath…]